These timpani were popular in Britain at the start of the 20th century. Here is a photo of Sir Edward Elgar conducting the London Symphony Orchestra at the Queen’s Hall in 1911 just a year before their famous ground-breaking trip to New York. The timpani in the photo appear to be very similar indeed to my Hawkes drums. Although the LSO’s maximum volume was probably quieter in 1911 than it is today (especially the brass) it might be surprising to think that timpani like this could ‘cut it’ in a modern symphony orchestra but undoubtedly they could.

These timpani were popular in Britain at the start of the 20th century. Here is a photo of Sir Edward Elgar conducting the London Symphony Orchestra at the Queen’s Hall in 1911 just a year before their famous ground-breaking trip to New York. The timpani in the photo appear to be very similar indeed to my Hawkes drums. Although the LSO’s maximum volume was probably quieter in 1911 than it is today (especially the brass) it might be surprising to think that timpani like this could ‘cut it’ in a modern symphony orchestra but undoubtedly they could.

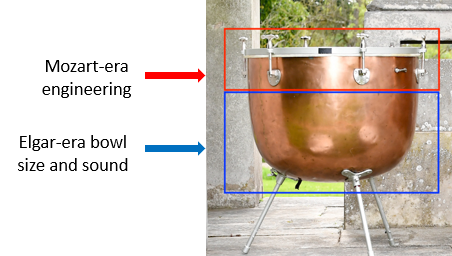

The presence of tuning taps might make one think that these drums are suited to early-ish music?

But surely the most important thing with any instrument is what it sounds like? And these drums sound very different to the drums of Mozart’s day. The major difference is that the bowls have been made deeper to increase the decay and maximum volume.

And so we must conclude that these drums are hybrids. Although smoother and slicker the tuning system uses essentially the same engineering as was available in Mozart’s time.

The collars remain small as per earlier drums but due to the volume of the kettle thinner heads work well providing a purer, more modern sound with longer decay. Permanent built-in legs have also been added.

Potter’s cavalry timpani

The tuning system is extremely similar to small 18th century timpani.

Potter’s cavalry timpani

But the bowls are much deeper than earlier timpani.

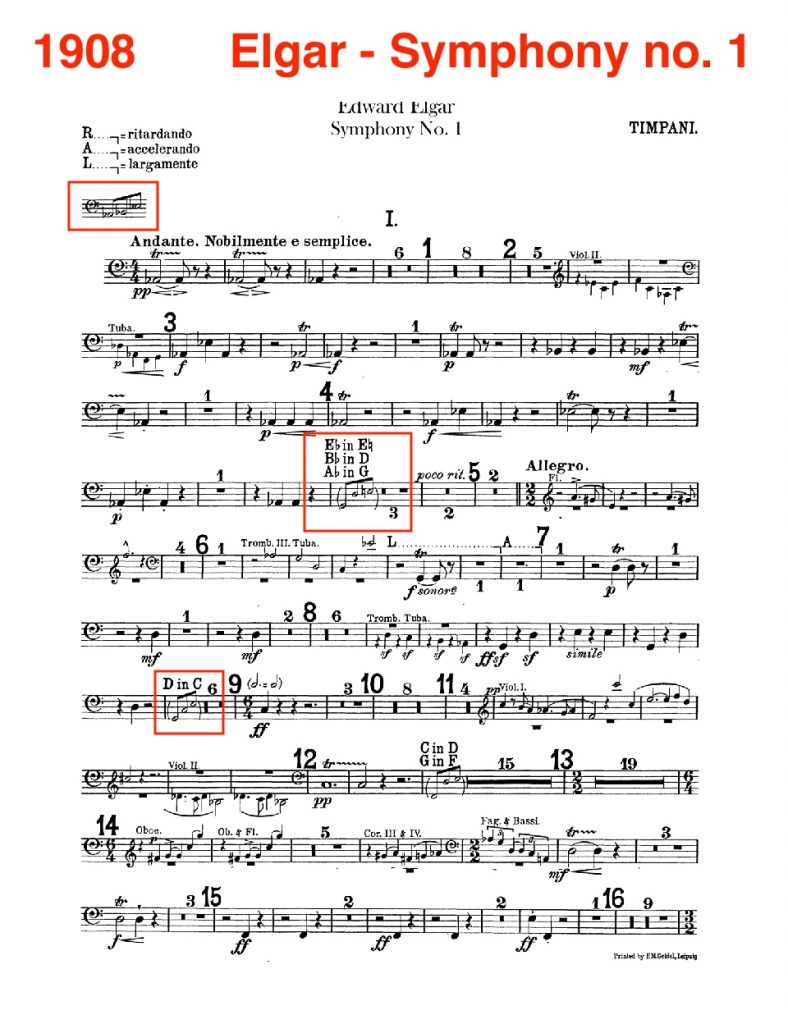

And so although orchestration and timpani techniques had advanced significantly in 200 years, Elgar was restricted in his options to write harmonically (as timpani parts were becoming by 1900) due to the primitive tuning system. In all his parts one can see where choices have had to be made where, for example, some notes were replaced by ‘less-than-ideal’ ones or left out altogether. Something that one cannot say about all composers; Elgar certainly understood the instruments at his disposal and his writing is still dramatic but intelligent to work within some boundaries.

What is intriguing is whether these instruments frustrated Elgar. Perhaps he was happy to write as he did, giving the timpani a role it could fulfil given the speed of tuning available? If you don’t require a more complicated instrument in order to play certain music then why go to the trouble of inventing one?

Not just limited by the tuning system Elgar most often seems to write as if the player only has three drums. Although this is undoubtedly restricting there is one major and shrewd advantage in that writing for small, realistic forces means that your music is likely to be played more often by amateur and youth orchestras.

The tuning changes in Elgar’s 1st Symphony are similar in speed and difficulty to the tricky quick changes Mozart writes in the Act II Finale of Cosi fan Tutte.

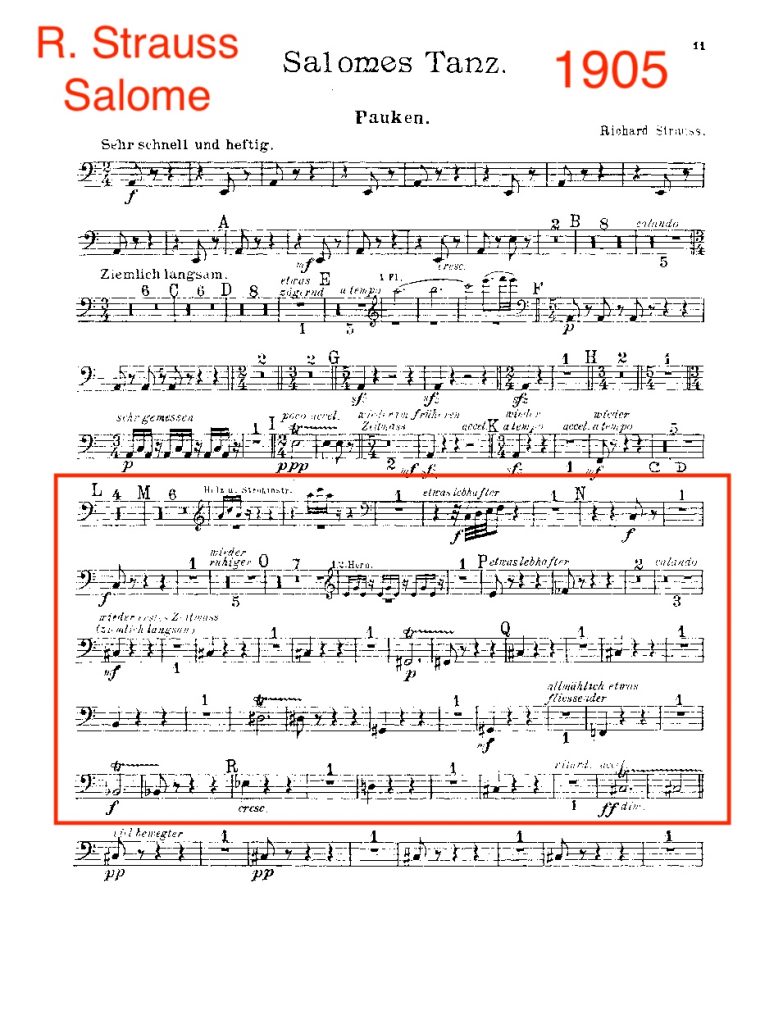

It is interesting to compare Elgar to what Richard Strauss was writing for timpani at the same time.

Schnellar timpani

Schnellar timpani tuning handle

Probably inspired by the new fast-tuning single-crank Schnellar timpani, the writing in Strauss’ operas (including Salome, Der Rosenkavalier, Elektra and Die Frau ohne Schatten) was radical and ambitious; these parts are today still amongst the most technically challenging that we have to play.

Utterly different to Elgar here the timpanist must find 12 different pitches in a section that lasts just a couple of minutes. And another huge difference to Elgar; Strauss surely must have been aware that through his enormous orchestration (including such unusual instruments as the heckelphone) and fiendish technical demands across the whole orchestra, many of his larger works could only be performed by the largest and most elite orchestras and opera companies.

So… are these deep English hand-tuned timpani any good? Well, some would quickly say no. In some ways they are the worst of both worlds as they are not ideally suited to any context one might encounter today. They definitely possess the slowest tuning system of all the available types of large-bowl timpani ruling out their use for certain late repertoire as we see above. And concerning earlier repertoire; although the tuning system and relatively small collars are ideally suited to this, generally the bowls are far too big for smaller ensembles playing this music.

On the other hand there are way more timpani parts like Elgar than Richard Strauss, so unless you are playing one of those unusual parts with fast, complicated tuning these timpani are perfectly good for most repertoire with a reasonably large orchestra. Compared to pedal or single-crank drums they are much lighter and so more portable and they are very much more affordable. With the use of small gels in the middle of the heads some excess decay can be taken away for smaller ensembles playing earlier repertoire. I tend to find it works best to match the resonance of the bowl with the resonance of the head (note; the small collar is ‘out of sync’ with this), and so this explains my preference to use thin modern heads. And so while gels reduce decay and volume and clever stick choices can be made, deep drums with thin heads can never achieve a really true baroque or classical attack and sound.

I have two pairs of these drums; 22″ & 24″ and 25″ & 28″ making a set of 4 and they are currently fitted with fairly thin English calf-skin heads.